I missed publishing last week because I had to write this Indexheads post, so my slightly humble apologies. This week I finally wrote about the creator economy, a topic I had been thinking about for months because I think this is a profound shift in the nature of work. I would have liked to keep things short but the last two issues became long because of the fascinating nature of the topics. As I started writing this post, the deeper I started going down the rabbit hole, and this is the other reason why I couldn’t publish last week. This topic was fascinating and so much fun. I hope you enjoy it.

Since the post is too long, it might break in your email. You can read it in your browser or by saving it to your Pocket or Instapaper.

Top of the news

The creator economy

The history of work can be described as banging things. God created man on the 7th day, and from day 8 onward, they started banging and rubbing rocks. This was the first job in the history of humanity. Then humans got bored and started banging and scratching the ground, a few birds above pooped some seeds, and humans discovered agriculture.

Tired of constantly being harassed by wild sheep, goats, oxen etc., the humans decided they had enough and went to war with them at the battle of Bakras. The cows, sheep, and oxen surrendered and entered into a live-in relationship with humans, and animal husbandry was born. After a while, they started scratching things and throwing stuff against walls. One day, a lady saw one of these things and went, “Hey, that looks nice”, and so art was born. One day In Andalusia, there was a guy who wanted to go poopie badly, but there were no lakes nearby. So by accident, he made a container by mixing clay and water, and so, pottery and crafts were born.

Meanwhile, lazy people in Europe wanted to work less. So they figured out how to standardize work, and factories were born. Every day humans woke up, went to a factory, banged things with a hammer until they died. Lazy humans kept inventing more machines and automated more work. This was called the industrial revolution. Humans went from banging stuff to banging machines. But soon, the machines learnt how to bang stuff on their own, and humans became jobless. They needed something else, and so the knowledge economy was born. Humans went from banging stuff with hammers to banging keyboards and started saying weird things like:

Professionally maximize proactive adoption. Credibly matrix best-of-breed technologies. Synergistically impact fully tested portals. Phosfluorescently myocardinate backend sources

As more things got automated, humans had to get louder keyboards, dual monitors to pretend to work harder to get attention. This has been the evolution of work up until now. The standard definition of a job of using a dual monitor to pretend to be doing twice the work and loudly saying the word synergy 16 times a day from 9 AM to 6 PM no longer holds. AI, ML, Blockchain, quantum computing, edge computing, robots, CRISPR and other fancy technologies are making many jobs obsolete.

So, what’s the future of work?

Historically, technological advancements rendered a whole lot of jobs obsolete but created more jobs. But I’m not sure if that will be the case with the next wave of tech advancements. People are slaving away in dead-end jobs, saddled with heavy student loans with little to no benefits. This is a huge problem!

I see two paths. Govts will either create Universal basic income (UBI) programs to pay you to watch Netflix at home, or people will quit their jobs and try to monetize their talents. This is called the creator economy or the passion economy.

Many of these terms like the creator economy, passion economy, hustle economy, and influencers get mixed up. People have been creating things and selling them since the dawn of humanity. Kings and queens used to offer patronage to poets, writers, artists, dancers and jesters. These people were the original creators and influencers. So this is nothing new.

This continued through ages into the internet era. But it was tough to make money on the internet. But with the rise of new tools and platforms like YouTube, Patreon, Glow, Substack, Gumroad, WordPress, Stripe, among others, creating and monetizing talent is easier than ever. Today you can make money through ads, subscriptions, sponsorships, merchandising etc. To do these things, you don’t have to suffer by building everything. There are readymade solutions.

Kevin Kelly’s now-legendary piece in 2008 was a prelude to the rise of the creator economy.

To be a successful creator you don’t need millions. You don’t need millions of dollars or millions of customers, millions of clients or millions of fans. To make a living as a craftsperson, photographer, musician, designer, author, animator, app maker, entrepreneur, or inventor you need only thousands of true fans.

And thanks to the internet, there has been an explosion in tools and platforms, being a creator is so much easy.

One fine day YouTube figured the word “creator” sounds better than “YouTube star”, and so the term “creator” became mainstream. YouTube exploded, and the venture capitalists saw an opening, and they bloody co-opted the term brilliantly. They’ve poured billions into startups building things for the creator economy.

Though the term sounds fancy, simply put, creators are individuals who monetize their talents like writing, singing, digital art, podcasting, streaming and so on. It could be through ads on Youtube, direct payments from readers on Substack, Patreon, gaming on Twitch, merchandising, events, etc.

The Creator Economy and NFTs are massive human potential unlocks. Even if certain assets are in a short-term bubble, we are on an inexorable march towards individuals mattering more than institutions. We’re on the precipice of a creative explosion, fueled by putting power, and the ability to generate wealth, in the hands of the people. Armed with powerful technical and financial tools, individuals will be able to launch and scale increasingly complex projects and businesses. Within two decades, we will have multiple trillion-plus dollar publicly traded entities with just one full-time employee, the founder.

Why the hell should you care about this creator economy nonsense?

The nature and the meaning of work are changing. Emerging technologies like automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML) will make millions unemployed, and we already see signs. This will lead to existential questions like what will happen to these people? Where will they find work? What’s the role of the govt? The creator economy could be a small solution to the unemployment problem. Being a creator today is still a tough but viable career path.

The internet has been a great equalizer. It has opened up the same set of opportunities to pretty much everyone around the world. Can you imagine recording and hosting a video before YouTube? It was a nightmare. Today, it’s not only easy to record and upload videos, but you can monetize them through ads and direct payments on YouTube with just a few clicks.

Any talk of the creator economy today is incomplete without a mention of the “Metaverse”. There’s no standard definition of what the Metaverse is, but here’s a thought experiment to understand it. Take the real world and your real-life and imagine an identical virtual world, an exact replica of the real world complete with all the digital identities, social structures, contracts, systems and economies. A virtual world(s) where you have a life just like you do in real life where you can live and make money? Think of those worlds in movies like the Tron, Ready Player 9, Avatar etc. Now imagine then being 100 times more real, complex, and layered.

It sounds like sci-fi bullshit, doesn’t it? Well, it often is, until it isn’t. We’re already seeing bits and pieces of this. For example, games like PubG and Fortnite are narrow virtual worlds with their own economies. People are selling virtual plots of lands on the Ethereum blockchain where you can build your virtual houses, malls etc. There are synthetic virtual streamers controlled by humans with their own unique identities making money.

This sounds a bit fuzzy because it is and hence the difficultly in explaining it coherently. But these digital economies are real, and creators are making real money. NFTs, no matter how ridiculous they seem today, are another example of this.

Today people are building multi-million dollar business with nothing but their mobile phones. The internet has removed most gatekeepers, not all but most. There was a steady rise in the number of people quitting traditional jobs and becoming creators and influencers. But the pandemic supercharged this shift. As Kevin Roose recently wrote in an NYT piece aptly titled “Welcome to the YOLO Economy“:

If “languishing” is 2021’s dominant emotion, YOLOing may be the year’s defining work force trend. A recent Microsoft survey found that more than 40 percent of workers globally were considering leaving their jobs this year. Blind, an anonymous social network that is popular with tech workers, recently found that 49 percent of its users planned to get a new job this year.

Allison Schrager wrote about the rising number of new small business applications:

That might seem counterintuitive. After all, the past year was exceptionally hard on small businesses, leading many to shut down. But the number of new business applications from the U.S. Census is up 38% compared to the year before the pandemic.

All of this is brilliant. But while there’s an almost a romantic tinge to conversations about the creator economy, not everything is as easy as it is made out to be. Several serious and profound issues don’t nearly get enough attention. The reason why I wanted to write about this is because of the thick layer of fancy bullshit that surrounds discussions about the creator economy. While a ton is written about how profound a shift this is, not a lot is spoken about the downsides and the risks.

So here’s how I see the creator economy and why you should probably think about it.

Winner takes all

Today’s creator economy is a winner take all system. You have writers and artists on substack, YouTube, Onlyfans and TikTok making millions. But the reality is that 80-90% of all these dollars go to the top earners. On substack, most of the writers who make money are people who already have built audiences like Bill Bishop and Glenn Greenwald.

Sure there are people like Packy, who writes the amazing Not Boring or Mario Gabriele of the Generalist. But such creators are by far and few.

For every Packy, there are thousands of writers who hardly make a few hundred dollars (a few thousand rupees) at best, not nearly enough to make a living. In a post published in February, Hamish McKenzie, the Co-founder of Substack, wrote:

There are now more than 500,000 paid subscriptions across Substack, and the top ten writers collectively make more than $15 million a year. It’s still early days, but this thing is happening.

What’s lost in translation is that the $15 million probably makes up a big chunk of the total subscription revenue on substack. With this $15 million going to the top 10, the rest is shared among the long tail of writers, which is peanuts. It’s the same with YouTube. There are probably just a couple of thousand Indian channels with more than a million subscribers. Worldwide, there are just about 230,000 channels with more than 100,000 subscribers and over 37 million channels with 10-1000 subscribers. Here’s how much you can approximately earn on YouTube, and this doesn’t include the 45% cut YouTube takes.

To get 50,000 views daily, you’ll need a couple of lakh subscribers easy. Even then, at the higher end of the earnings range, which is quite generous, it’s hard to make a living. To make over $50,000 (Rs 36.5 lakh) in a month, you need to have at least 20+ million (2 crores) subscribers according to this ET article:

Currently, Nagar has more than 25.7 million subscribers on his channel CarryMinati. The report also estimates his monthly income from the platform at around $66,100. This does not include income from corporate sponsorships, merchandise sale, or fan donations.

On Only Fans, which has become the go-to destination for adult entertainers, the average earning is only $180 (Rs 13,000).

On Patreon, the poster child of the creator economy, only 4300 people made at least $1000 (Rs 72,400) a month, according to this 2019 article. Even if you triple that number, it’s nothing.

Patreon doesn’t disclose how many $1K Creators there are, but CEO Jack Conte said “It’s a tiny portion. Because it’s an open platform, we at one point had hundreds and hundreds of thousands of creators who were making $0.” By the estimates of Graphtreon creator Tom Boruta, there are currently more than 4,300 creators making at least $1,000 per month (and more than 9,200 creators making $500+ per month). That small subset — 4,300 out of 132,500 active creators or about 3.2 percent of its customers — is Patreon’s core focus nowadays.

Being a creator isn’t a walk in the park. The sales pitches for creators often make it seem like all you have to do to make millions is post a video and start counting the dollars. Being a creator is just like starting a small business; the success rates are abysmally low. What the creator economy needs, as Li Jin wrote, is a way for the long tail of small creators to flourish. Today, just like in the real world, there is gross inequality in the creator economy.

But for content platforms, the move to digital content hasn’t been correlated with a burgeoning long tail: the top creators are massively successful, while long-tail creators are barely getting by. On Spotify, for instance, the top 43,000 artists—roughly 1.4% of those on the platform—pull in 90% of royalties and make, on average, $22,395 per artist per quarter. The rest of its 3 million creators, or 98.6% of its artists, made just $36 per artist per quarter.

Today, for most people, being a creator is, at best, a small secondary income.

Social safety nets

Working in companies might be soul-crushing for some. But at least some companies provide benefits like retirement savings plans, health insurance, paid leaves, wellness programs etc. Despite companies offering retirement plans, many countries are starting a retirement crisis. For decades, politicians and regulators kept kicking the can down the road and didn’t take action. Pension funds across the world today are staring at trillions in shortfalls. As developed societies head into the Twilight, they’re are walking into a humongous crisis. The pension crisis will be a defining challenge of our times, like climate change.

But as more people become creators, the question of a social safety net becomes an even important one, especially in a low-income country like India, where the government is in no state to provide benefits to large swathes of the population. Even today, India suffers from dangerous levels of unemployment, particularly among the young people, the same people who tend to become creators.

If the long tail of creators barely make enough to make food and rent, how will they get by in times of emergencies without a social safety net? If creators are to flourish, there has to be a fundamental rethink of the existing labour policies. Governments should start looking at the creator class as a legitimate source of employment. Given that our politicians mostly tend to be old, useless, and more worryingly Luddites, this seems like an unlikely possibility.

This current generation of old politicians have to die soon if this ever becomes a priority. But in all likelihood, a Universal Basic Income (UBI) seems like a large part of the solution.

Regulations

The regulatory void surrounding creators is the most pressing issue of the moment. The reason is that the relationship between creators and supporters tends to be intimate or, as Kyle Chayka writes: parasocial. So the opinions and recommendations of creators tend to hold a lot of sway.

Similar to influencers, creators tend to be big personalities, people who audiences want to feel close to not just because of their content but their presence through the screen. As much as they discuss and promote their art, creators talk about themselves: their apartments, skincare routines, and self-help practices. Cloaked in the guise of a highbrow cultural product, what they really offer is presence and intimacy. “Parasocial” is another increasingly popular term for the kind of one-sided emotional relationships audiences develop with actors or podcasters — the creators who have kept us company during the pandemic.

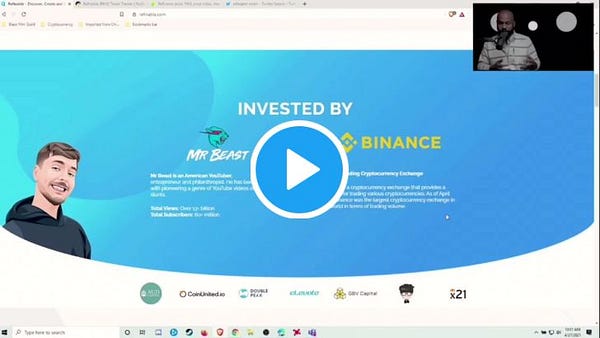

If you noticed, the terms creator and influence just got mixed up. Theoretically, a creator creates and monetizes things like newsletters, fitness videos, and songs. An influencer monetizes his or her fame through sponsorships and ads from brands. But in reality, the lines are blurry. But, both creators and influencers have incredibly loyal and rabid fans who take things that these creators and influencers say seriously. Several of these people, influencers, in particular, have used these relationships to sell harmful things like conspiracy theories, peddle fake news stories, dubious diets, vitamin supplements, beauty products and even cryptocurrency schemes. Not to forget, boner pills.

As Kat Tenbarge of Insider alluded to on a podcast:

As the industry matures, and some creators gain massive wealth and power, it’s inevitable that some will abuse that power. But when that happens, what can be done? On the internet there are no gatekeepers, which is the reason there’s so much original amazing content that we all love. But there’s also a downside. Too often there’s no one there providing accountability for harmful and abusive behavior.

Influencers peddling dangerous things is a problem in India too. Several newly minted influencers are shilling stock tips, stock market tutorials, trading courses, and health fads on YouTube without understanding a damn thing. Their followers blindly follow anything these people say without a second thought. These influence can say anything because there’s no liability if something goes wrong. The regulators and regulations haven’t kept up with this evolution in advertising.

Surprisingly, the Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) issued guidelines asking influencers to label promotional content. But globally, regulations need to do a lot of catching up.

Any idiot today can be an influencer, and that’s a scary thing:

But in the 21st century, the rise of social media has created a whole new career opportunity for people with fewer brain cells than the money I have in my bank account. Nowadays, you can become an influencer.

Mental health and creator burnout

Creators and influencers tend to be disproportionately young, and they are quite vulnerable to the trappings of fame. Take a look at the results of this survey commissioned by Lego. When I was young, if someone asked kids, what they wanted to be when they grew up, the common answer used to be a doctor, engineer or cricketer. But times have changed; kids want to be YouTubers, TikTokers and Instagrammers.

Today, the most famous influencers are teens, and they spend a disproportionate time on social media platforms like Instagram and now TikTok.

And these platforms, TikTok, in particular, have become hit factories. Teens can go viral overnight. Over 25% of users on TikTok are under 19, and the numbers tend to be similar on Snapchat and Instagram. Take the case of Ryan Kaji, he’s just 9, and he made over $30 million on YouTube. TikTok sensation Charli D’Amelio is just 17, and she makes more than $4 million a year. Even teens with smaller accounts make thousands of dollars every month, more than most formal jobs. Most of them aren’t ready to deal with the demands of overnight and fickle fame.

Stars come and go. These teens feel euphoric when their follower count is rising and get seriously depressed when the ticker stops.

And that’s only if you become famous enough to get lucrative brand deals. For the majority of kids who go viral on TikTok, the attention doesn’t last. “I wish I never got this sort of fame,” a 16-year-old former TikToker named Sam told me last year. He’d been creating delightfully bizarre videos that earned him a following of nearly 200,000, until suddenly the view counts started to drop and it felt like the audience didn’t like him anymore. He left the platform and sought therapy for the anxiety he’d developed due to TikTok.

Lots of TikTokers bring this up. They’re afraid of branching out from whatever the algorithm decides it likes for fear of becoming a has-been, and they’re burned out by the churn of endlessly creating content they barely even like. Some have public meltdowns, others quit for good, while even the app’s biggest star Charli D’Amelio said she often feels overwhelmed by the constant negative attention.

The modern influencer is a commodity and is easily replaceable. For brands, these teen influencers are just follower counts and engagement metrics. The human element of the influencer doesn’t matter. In the past few years, several influencer marketplaces have cropped up. Brands can shop for the influencers they like, just like you shop on Amazon. The human element is all but abstracted away.

When teens who are nowhere close to being ready to deal with the pressures of the influencer economy have to compete in such an environment, the number of things that can go wrong is endless. Depression, anxiety, suicidal tendencies are rife among these teens. The kids were supposed to be the future, but they are nervous wrecks who barely function.

Professor Barrett Swanson, in his recent Harper’s piece, sums this up poetically:

For a moment, I cannot remember who I am or why I am sitting here amid this sea of beautiful young people, all of them desperate for recognition, their whole lives ahead of them, empty at the absolute center. TikTok is a sign of the future, which already feels like a thing of the past. It is the clock counting down our fifteen seconds of fame, the sound the world makes as time is running out.

The gatekeepers

Now coming back to the earlier point I made about gatekeepers, the internet has diminished the role of old gatekeeps like ISPs, agents, editors, and cultural referees. Today, the tech giants and algorithms have emerged as the new gatekeepers. Unless you’ve built your business entirely on your website and own your audience, you’re at the mercy of Twitter, YouTube, Facebook and their algorithms.

Debates over whether big tech is good or bad always lack nuance, and people hastily jump to conclusions. I’m going to do neither. Unpacking this debate requires nuance, which is beside the point of this post.

Social media platforms are businesses, and they are in the business of selling dopamine hits. Your attention is their raw material. To extract it, they need to keep you hooked. So they keep supplying you with more and more powerful dopamine hits through recommendations that appeal to your tastes.

In the early 2010s, Facebook was driving massive traffic to pages, and creators built enormous audiences on their pages. One fine day, Facebook decided to prioritize friends over pages and traffic to pages cratered overnight.

Facebook wanted to do video in 2015 and started driving traffic to videos. People bent over backwards to produce videos for Facebook, and in 2018, it changed its mind. Brands and people who were spending millions making videos went bust. Millions of people had built followings on Vine, Twitter acquired it, neglected it and shut it down. People lost their audiences.

What works on TikTok and Instagram keeps changing every day depending on the moodiness of their algorithms. Add to this the constant launch of new platforms on which creators have to jump and start dancing. Creators and influencers are nothing but monkeys dancing to the whims of the platforms. The rise of the creator economy is no different. Brands know that this creator and the influencer economy will probably be big, and they want a piece of the action. Platforms like YouTube, Snapchat, and TikTok have announced creator funds with $100s of millions to pay creators and influencers to be on their platforms. Creators will now chase this carrot until they finally get the stick.

Comedian Matt Ruby summarized it best:

“Reels get more views and that helps you take down a competitor? Yessir, we’ll hop to and start making Reels.” Um, when did we all start working for these behemoths? It’s gross that Zuckerberg snaps his fingers and just like that an entire artform shifts directions simply because it helps IG do battle with TikTok.

But:

I mention this only to observe that if we sneer and snicker at influencers’ desperate quest to win approval from their viewers, it might be because they serve as parodic exaggerations of the ways in which we are all forced to bevel the edges of our personalities and become inoffensive brands. It is a logic that extends from the retailer’s smile to the professor’s easy A to the politician’s capitulation to the co-worker’s calculated post to the journalist’s virtue-signaling tweet to the influencer’s scripted photo. The angle of our pose might be different, but all of us bow unfailingly at the altar of the algorithm.

Having said that, imagine yourself being a creator in a world without platforms. Imagine how hard it would be to build a following. I write two newsletters – this and Indexheads, which has about 2700 subscribers. All the subscriber growth has been predominantly due to sharing on Twitter. Without it, I’d have long stopped writing. The same goes for pretty much all creators. The money they make today is largely in part due to the platforms.

I’m not saying that we should all be thankful and dance to their tunes, but what are alternatives? These crypto crazies often go, “blockchain can solve that”. And we’re seeing the first wave of decentralized platforms like Mirror, Bitclout, Mastadon, etc. Maybe one day, they will be the new Twitters and YouTubes and Substacks, but that day is far away. Until then, despite all the shenanigans of the platforms, creators have very little choice but to live with these trade-offs.

Subscription fatigue

This is a tricky topic. In the past 5-10 years, starting with news publishers and streaming services, more and more products and services have become subscription-based. The menu of subscription-based offering has only grown with the creator economy. This has led to a debate on whether are too many subscriptions competing for a limited wallet share and if this is causing a subscription fatigue among consumers. On the face of it, you can make an argument that consumers on average have X dollars a month, and if there are Y number of products competing for those dollars, how will creators make money?

On the one hand, you have a consumer-centric view link this one

On the other hand, you have creators like Simon Owens, who publishes a brilliant newsletter on Media and Ben Thompson, who writes the awesome Stratechery, who think this is a non-issue:

Simon Owens: I think subscriber fatigue is a little bit overrated and a little bit overplayed in terms of a worry for it. The reality is, the vast majority of your subscribers are going to be the free subscribers, and you’re just going to be converting your most obsessed users into it. And if you do the math, let’s say there are a billion people in the English speaking world and on average, each one only subscribes to one publication, there are so many different ways you could splice a billion subscriptions in terms of how many creators that could support.

Ben Thompson has another way of putting it where it’s like, people tend to underestimate how many people are on the internet. There are so many people out there that it is possible for a lot of different newsletters to find their thousand true fans. Don’t get me wrong, it’s so hard, there’s going to be so many people who try it and fail. But it is possible.

I like Matt Ball’s phrasing:

The “subscription economy”, by definition, presumes that the overall “economy” – from products, to services, content, transportation, labor and more – is shifting over to “subscriptions”. Thus, to claim that consumers have “subscription fatigue” is to say that they have “spending fatigue”.

I personally agree with the creators. This world is big enough for creators to find their 1000 true fans. But what is true is that with more creators vying for the same dollars, the best product will always stand out and grab the dollars.

All of this seems like a lot of whining and complaining about the downsides of the creator economy, and you’re probably right. But this current iteration of the creator economy is similar to the real economy – there’s too much inequality. And with the VCs now having turned their money-grubbing gaze toward this space, the sunshine and roses narratives like the creator economy will transform everything and make everyone rich tend to grab headlines. Narratives that take a critical look won’t get much play, and that’s one of the reasons I wrote this. I have a horse in this race because I write a newsletter, and if I try to monetize this one, for example, I have to contend with the same challenges.

In spite of all my whining, I think the creator economy is a net positive. Today, it is much easier than ever for people to monetize their talents, and if they’re successful, they can make a good living, doesn’t mean it’s easy. But there are real structural issues that need some serious debate. Because this is a profound shift in the nature of the work and our antiquated systems and regulations, which were crafted for a time that is long past, are ill-equipped for the current times.

Rabbit hole

This rise of the creator economy and the implications is in itself a mega rabbit hole. In spite of the 4000+ word attempt at exploration above, I’ve barely scratched the surface. If you’re really curious, a few sources to go down the rabbit hole.

Li’s newsletter

Taylor Lorenz’s Newsletter

Digital Native

Matthew Ball

a16z

Category Pirates

Arm The Creators

Creatorscape

Not Boring

Medialyte

Neiman Lab

Means of Creation

David Perell

Trends, Analysis, Lies and Statistic

Chief Content Officer

Good reads

The arguments of the techno-pessimists are not specious or ridiculous — indeed, they are very powerful. There’s no denying the reality of the recent productivity slowdown, or the fact that it’s getting more expensive to get scientific results (at least within specific fields). Techno-optimists have a very difficult task — predicting not only that the trends will reverse, but identifying which specific technologies will enable that reversal.

Periods like these often end badly, especially for ordinary investors. Mutual funds of the twenties became so over-leveraged that, once the stock market began declining in 1929, the funds accelerated the worst crash in American history. During the credit-card craze of the sixties, unsolicited cards were mailed to felons, toddlers, and—in at least one case—a dog

The author of the article, Spencer Jakab, cites an analysis that claims that the average actual investor in ARKK is now trailing the S&P, even though ARKK is still up more than 2x over last year. The reason is that most of the current investor base jumped into ARKK after the fund put up the biggest returns, just in time for the recent fall.

A wealthy family or institution like a a university have similar needs. Use a small percentage (4-5%) of the corpus to meet expenses and commitments and let the portfolio grow. And since your liquidity needs can easily met by allocating a small percentage to liquid assets, a large percentage of your portfolio can invested in things that the ordinary investor cannot.

4. Three Things I Think I Think – The More Things Change the More They Stay the Same

Maybe I am biased because I spend too much of my time trying to manage financial risk, but this all has a very “free lunch” feel to me. For instance, let’s say the government responds with big fiscal stimulus the next time the economy and markets get a whiff of recession. Well, the markets will roar back to life in anticipation. They’ll become more overvalued than they already were. And one could argue that this stability will breed future instability.

Related read: Lots of Liquidity

5. Dubious dealings at property tech startup Strata

Strata, in its financial model deck, misrepresented an IRR calculation. (IRR is short for internal rate of return, a metric used to measure financial returns for various asset classes.) The deck for every asset goes to investors to help them make a decision. According to several of the employees we spoke with, Strata showed an IRR of around 20% on the project “that was not delivering more than 13.5% IRR”.

6. Why today’s highfliers are so likely to fall back to Earth

While there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that significant parts of the stock market are being driven by speculation rather than investment, we don’t need to rely on anecdotes for a demonstration. The explosion in the use of derivatives that are purely speculative in nature shows a stark change in the motivations of a significant fraction of market participants. It is almost unquestionable that speculation is a much bigger driver in the stock market today than is normally the case. Speculative booms are not guaranteed to end badly, but they normally do and that seems to be particularly true in the stock market. I’d argue that an important cause of this eventuality is that the stock market is adept at giving speculators what they crave, and scarcity is necessary to keep prices above their fundamentals for an extended period.

7. The Stock Market Is Suspiciously Well Behaved

The dramatic gains of the last 12 months can be accounted for almost entirely in terms of rising earnings expectations, which is exactly what all the textbooks say should happen.

Playlist

Remains of the week

Decimation of India’s white collar jobs. Sustainable bonds demand picks up in India. Old white senators say no to Bitcoin on Wall Street. Is activism a better version of ESG?. The best place to hide Bitcoin mine is inside a Marijuana farm. Pied piper needed down under. AMC Raises $230 Million From Equity Sale. Will Value investing rise from the ashes like a phoenix or is it a head fake? Brazilian Inflation. It could take generations to unwind quantitative easing. How Movie Sounds Are Made.